The Sopranos as Greek Tragedy: The Many Saints of Newark Review

Muddled on its way to metatextual catharsis, The Sopranos prequel is a sentimental postscript (only) for the fans.

Warner Bros. Pictures/HBO Films’ first trailer for The Many Saints of Newark. Misleading snippets of a messy film.

Caution: The following review contains multiple spoilers about both The Many Saints of Newark and all seasons of The Sopranos.

Strung together like the sausages at Sartriale’s, footnotes abound in David Chase’s prequel to the series one critic subtitled, “the Great American Novel, and it’s 86 episodes long.” A pale replica of what’s (inarguably) the closest television ever came to art, The Many Saints of Newark seals its fate with serial imitations of the show’s signature moves: whether it’s Paulie coming through the door with “O-oh”, jump cuts from assaults to upbeat songs, close-ups of marinara-laced spaghetti or the trend of killing kin in cars.

Earthly tones of taupe and carpet-brown tilt The Soprano family’s surroundings in the sixties to a one-note hue: a palette saturated with the shades of teal blue, beige and chestnut. The display is oddly homogeneous compared to the much motlier and slowly darkened eight years of the series, symbolising - like a faded beach shot on a postcard - a dilution of once-dazzling visuals.

Relying on a host of struggling and at times subpar performances, violence occasionally gratuitous and ill-considered camera angles, The Many Saints of Newark comes across as an examination by a fan who stands out waiting in the Meadowlands’ downpouring snow in an inane bid to approach the series’ legendary creator, David Chase (he doesn’t live there).

A pity all the more – since it’s a film scribed by said legendary creator David Chase, together with occasional Sopranos writer Lawrence Konner.

Skewing far from the beloved series in both quality and theme, The Many Saints of Newark marks its difference to the show’s style in its opening scenes. The camera hovers in and out of snow-topped graves across a cemetery as a host of voices kvetch and babble: confessions (or, in this case, openly voiced agita) of the unsilent dead. Coming to a headstone topped bizarrely with a coloured shot of Christopher – in case you forgot what he looked like – it stumbles on an introduction obviously written for the uninitiated: not quite “Hello, my name is Christopher Moltisanti” but a similar cliché.

Immediately Tony is presented as his nephew’s “murderer”: “The guy I went to hell for.” In a surprising plot twist, Christopher has garnered in the afterlife an eloquence that tragically eluded his stoned, budding playwright self. In the middle of the picture’s second act he comfortably evaluates, “This move made Tony half a pussy in my estimation.”

Death appears to have roused someone hard-pressed to awaken when alive.

Lugubriously laden with the shades of grey and charcoal, this beckoning of ghosts takes an abrupt lunge out of The Sopranos - where the perished surfaced only in the reels of perfectly compiled dream sequences.

It marks the debut “out of genre” gesture in a movie riddled with them. In director Alan Taylor’s hands, out of focus backgrounds and blurred shots make up a handsome portion of the film: much of the time, inanely. Christopher’s grandfather Aldo “Dick” Moltisanti (Ray Liotta) marries an Italian immigrant, Giuseppina Bruno (Michela de Rossi). Throughout Sunday dinner she is blurred out every time her husband speaks. Of course she takes a backseat to his “work” – but it’s unnecessary emphasis, and dizzying to see.

Similar distortions of the digitally captured motion picture saturate more scenes. When Tony’s father Johnny is at last released from prison and picks up his toddler Barbara in his arms, she’s made a hazy, indistinguishable figure. As a corrupt cop marches to a car we see the former coming up the tarmac from below: fuzzy feet obscured amidst a gluey gaze that could suggest a newborn kitten’s sight.

Eerily swaying curtains seem to want to mimic horror films; so does the stormy ocean in a later scene that might have come out of Cape Fear or Sleeping with the Enemy. CGI-ed fires make an artificial show and a close tracking shot of a fast-moving baseball calls to mind the feeblest feelgood, “family fun” movie. Consistency is lacking in a work where food becomes by far the most authentic aspect.

Scattered likewise in a host of differing directions, Chase and Konner’s script appears to channel The Sopranos but keeps stumbling off it. Hearing some parts of the screenplay is like watching an ex-roller-skater failing time and time again to climb the ramp.

Amidst some several dozen characters The Many Saints of Newark dithers when it comes to choosing on which family to cast a light. Harold McBrayer (Leslie Odom Jr.) is a small-time crook who shuns the Moltisanti crew to bolster the Black Power Movement and construct his own wrongdoing empire. Perhaps the only character to have a conscience, Harold highlights the injustices against New Jersey’s African-Americans and sparks the separate topic of the era’s race relations: an enormous theme beyond even the magnitude of The Sopranos. The subject is unfittable in this two-hour piece that spends some fifth of its mismanaged screenplay casting “wink-wink” nods at the show’s moments. Poor Harold and his family have several scenes squeezed out of the film’s body and enmeshed between the credits.

Elsewhere the characters are fleshed out just halfway: three quarters three-dimensional at best. Denseness defines our antiheroes much more than it did throughout the series. “I didn’t know there were Jews in the Middle Ages.” quips Dickie to a teenage Tony as he reads a comic book. What about “Denial, Anger, Acceptance” – the first season’s third episode in which the gang torments Hasidic Jews in order to secure a “get” (divorce) for an impatient business partner?

“You ever heard of the Masada?” One Orthodox man asks a threatening Tony. “For two years, 900 Jews held their own… against 15,000 Roman soldiers. They chose death before enslavement. And the Romans, where are they now?”

“You’re lookin’ at ‘em, asshole.” Tony points out.

Repartee of such a calibre is what defined the tongue-in-cheek wit of the series. Here it is watered down to jokes that wouldn’t even make the grade at wedding toasts: “While my brother’s away everything goes through me,” insists Uncle Junior (Corey Stoll). “You got diarrhoea?” jokes Joey Diaz’s Lino Bompensiero.

Revived after a gap of fourteen years by Chase and Konner, the six seasons’ delicious Italian-American lexicon is used maladroitly; grown stale like left-out panettone. Aldo’s twin brother Sal (conveniently also played by Ray Liotta) remarks to his nephew, “My brother’s hands were as soft as a baby’s peeshadell,” the latter being a term for “genitals”.

But who of The Sopranos gang would be referring to a baby’s genitals?

Misplaced are the innumerable references to the hit show in what is unashamedly a gallery of in-jokes: Christopher crying when the teenage Tony wants to hold him during Sunday dinner, prompting an old lady to remark, “Some babies, when they come into the world, know all kinds of things from the other side.” Aside from stressing something even unenlightened viewers know by this point (Tony’s eventual killing of Christopher), it’s a misguided portrait of their enmity. All fans will know the two had a tumultuous and turbulent, yet sometimes touching bond for many years.

At Aldo’s funeral Tony comments that “there was a bird in the garage” (an allusion to Christopher’s omen during his mafia initiation ceremony in Season 3’s “Fortunate Son”).

Elsewhere Junior states, “He don’t have the makings of a varsity athlete.” Again.

Relayed to a new cast with flimsier direction, the show’s characters must scrape by to survive. Liotta is ironically the weakest link among the cast as both Aldo and Sal Moltisanti; projecting one-note, brutish intonations for the first and stoic, pretend self-awareness for the latter. Eyeing the more metatextual Scorsese universe, he strives to lend Sal gravity ungranted by the script while evil Aldo is afforded squints to showcase his advanced age and fatigue.

Alessandro Nivola is one more target of the broken screenplay. Imbuing Dickie with much-needed rage, he rarely shifts beyond the two extremes of wrath and rancorous regret. Lightness is absent in this central character who lacks Tony Soprano’s empathy, endearingly duck-loving idiosyncrasies and humour. Livia becomes a shadow of her former self amid Vera Farmiga’s noble efforts. While certain repressed bitterness occasionally simmers to the fore, Farmiga’s likewise not assisted by a script that whittles the notorious strega down to a cankerous Italian mother loath to suffer fools. Absent a reference to the psychotropic medication Elavil, Sopranos non-fans wouldn’t know she suffered from a genuine disorder. The actress’s half-fashioned New Jersey (“New Joisey”) accent also drops off at intervals.

Michela De Rossi’s Giuseppina carves out one of the film’s sole endearing personalities: a Neapolitan and feisty, fatefully more ignorant rehearsal for the bolder Adriana still to come.

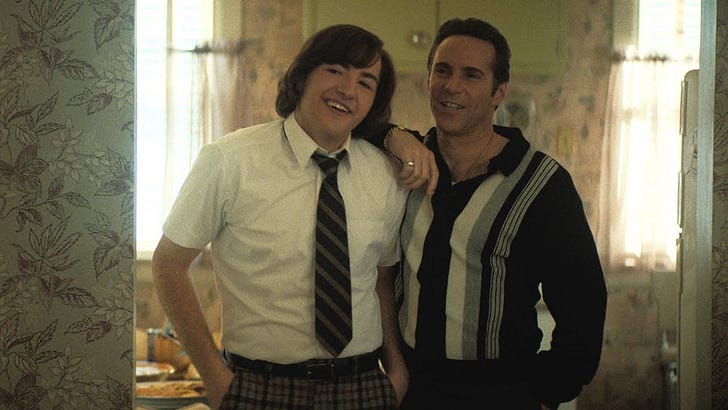

And The Sopranos’ leftovers are salvaged in the eyes of Michael Gandolfini - son of genius James - who plays his father’s antihero in his teenage years. Through the lanes of curly hairs along his arms, his stubborn way of standing with one hand tucked in his pocket, vulnerability arising in his “How you doin’?” greeting, he is Mini-Tony before Tony became Tony. Admittedly some phrases tumble off the plain of realism in the rookie actor’s juvenile performance (Gandolfini’s only other major credit is ten episodes of HBO’s The Deuce). And yet his manner even when he sings a ditty to one side – much like his father did with “South of the Border” in Season 1’s “Boca”, “Maybe Baby” in the second’s “Funhouse” – is one of the few throwbacks to the series’ naturalism.

Greatness so embodied the performers of the series’ main cast – Gandolfini, Edie Falco, Lorraine Bracco, Michael Imperioli, Drea de Matteo, Steven van Zandt and others – that where applicable their young counterparts emerge as little more than parodies in SNL. Crowned with a rapidly receding hairline, Corey Stoll is far too whiny and high-pitched even for Junior; Silvio in John Magaro’s hands – with downturned lips and that lisp-like enunciation – is a comic book-like replica.

Thankfully Little Janice (Mattea Conforti) manages to incarnate a self-to-be; offering that simultaneously sleepy, steely gaze as she sits watching Key Largo.

Greek tragedy is what allows us to remember this derived from The Sopranos. Where Tony went to weekly sessions to absorb the sermons of the critical Greek Chorus that was Dr. Melfi, Dickie here pays visits to his jail-housed uncle, Sal, for pellets of advice.

The forthcoming counsel falls short of the therapist’s suggestions – even at her least professional, drunk self. “Maybe some of the things you do aren’t God’s favourite.” avers Sal, the zen Buddhist. Refraining from confession, Dickie keeps insisting that he wants to do “good deeds” (this from a mass murderer-in-training). What ought to be the film’s most solemn moments slip into faint echoes of the show’s soliloquies.

Without displaying the entire plot it’s difficult to demonstrate just how The Many Saints of Newark turns the fate of the Soprano family into The Oresteia: a choice strange since subtlety and the unspoken made up the twin tenets of the show.

Here they are shunned in favour of direct, explicit explanations: Dickie is destined to repeat his father’s violence toward Giuseppina while his doting nephew Tony is invariably doomed to play out father Johnny and his uncle Dickie’s dangerous dynamic with the older Christopher. The dots join up. Young Tony clenches Dickie’s pinkie with his own and those famed beats of Alabama 3’s “Woke Up This Morning” are in earshot.

It would be caustic to suggest The Many Saints of Newark is a million miles away from its small screen originator: softer scenes like Tony plodding through a nightly snowstorm in a scarlet bomber jacket after Dickie snubs him lend the antihero even more compassion. At certain points the background details that enhanced the show are here accorded their due diligence: one of Dickie’s “businesses” is titled “Vulcan Vending Machine Co.”

But it’s a venture struggling (like the suffocating Christopher) for breath. In The Sopranos every piece of music was an expert choice for both its metatextual commentary and perfect timing: Tony re-enacts his sixties childhood of erecting sprinkle-laden ice cream sundaes to the tune of “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane; “Take Me To The River” haunts him after he shoots best friend-turned-informant Pussy, wraps him up in garbage bags and hurls him in the ocean.

Here we’re left with standard, overly known songs: Frank and Nancy singing “Somethin’ Stupid” and The Jackson 5 with “ABC”. “I’m a Man” by The Spencer Davis Group makes an appearance. Where The Sopranos laid bare arias rarely heard like “Che bel sogno di Doretta” from Puccini’s La rondine, The Many Saints of Newark takes the overused “Un bel dì” (“One fine day”) from Madam Butterfly.

The authors of the piece seem to have broken up the series into tiny, splintered tiles and tried to plaster them together in a clumsy reimagining of The Sopranos’ irreproachable mosaic. Even moments cited in the show that surface in the feature – Johnny shooting Livia’s beehive; his arrest while a despondent Tony and cool Janice look on at the kids’ amusement park (originally reconstructed in 1.7, “Down Neck”), resound differently.

Sombreness is the sole sentiment the movie offers as it chooses to re-part with characters we know and love lost in a world completely alien to us. In its last scenes the film morphs into a memorial: for the great James Gandolfini, for the long-gone art of cinema and for the recently fled Golden Age of Television. Tipping its hat like a saluting pallbearer.

For a show that ended fourteen years ago, this encore presentation of goodbye is just too much.