Saint-Saëns, Saint-Laurent, Bouffants and Tortoiseshell Glasses: Callas incognito in the early sixties

From "The Callas Imprint: A Centennial Biography," Chapter 13: "Little checking machines."

The scene: March 1961. Maria Callas moves to France, retouches her pronunciation, switches fashions and becomes even more vocally chameleonic.

Slowly Maria settled down in Paris—taking frequent trips between her Milanese abode and the metropolis that was Onassis’ hometown. Renting an apartment at the Hôtel Lancaster, 7 rue de Berri,1 she hopped peripatetically between the cities.

Fastidiously loyal to Biki,2 Maria craved the 1960s Saint Laurent collections (“It’s such a shame that this style doesn’t suit me,” she confessed) and adored Pucci.3 Now that garments were much looser and their colors flagrant and flamboyant, the soprano could be seen in strapless dresses, halterneck gowns, jumpsuits, waistless frocks and floral patterns. Her wigs embraced the range of “big hair” vibrancy: thick bob-dos, bouffants, flips and beehives. Topped with tortoiseshell glasses, the looks made for a humorous sight.

Without the services of La Scala’s maestro sostituto Antonio Tonini at her helm, Maria heard of vocal coach Janine Reiss through their mutual friend Michel Glotz. Preparations for a compilation album of French arias propelled her to arrive at the instructor’s decorous apartment on the rue de Courcelles. In retrospect the latter would recall, “I would say that Maria had lost—not her top notes—but her ease of reaching the top register: it had lost its stability.”4

Maria’s first move was to ask if Reiss had any neighbors. There was an old general at the Hôtel Lancaster who hated the sound of her practice; resorting to banging his cane on the ground when she vocalized. The answer came in the negative: only a deaf lady lived on the story above. Maria opened the score she had brought—Bizet’s Les pêcheurs de perles—and performed several arias. Upon completion she demanded Reiss dissect one of the piece’s tough cadenzas and explain the right way to interpret it.5

In a similar fashion Maria would bring along all sorts of scores—including her well-known Medea—and solicit advice: “Can you give me some ideas?”6 she would request. The women would spend hours going over the same page. It riled Maria when her coach did not immediately call out her mistakes. “But, Maria—I was waiting for you to finish the phrase before pointing it out!”

Reiss was later eager to aver that the soprano had possessed “an excellent technique: she knew how to breathe, to lift the soft palate at the right moment, and she herself could hear perfectly the sound she produced.”7

When one day fellow student Michel Hamel arrived to get a notebook he had left behind, he spotted the bespectacled soprano midway through her lesson.8 She greeted him politely. During his next visit he exclaimed agog to Reiss: “You know, Janine, that woman that I saw—she looks extraordinarily like Maria Callas!”

Never did the man discover her identity.9

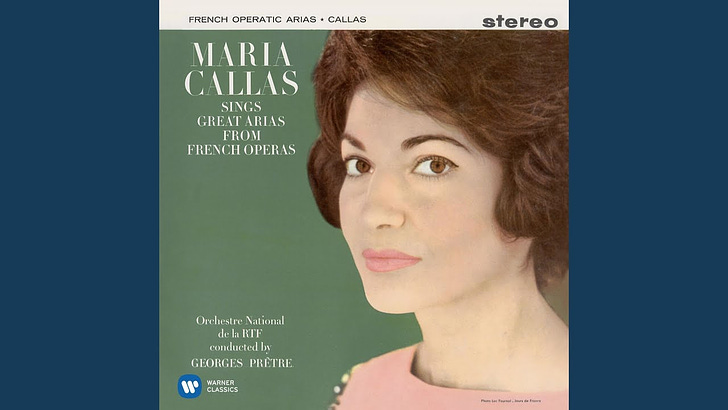

While Onassis toured with Winston Churchill once again on the Christina Maria prepared to record the French arias disc, beginning rehearsals on March 24th, 1961.10 For this endeavor she had carefully recruited a new favorite among maestri: young Georges Prêtre, who was almost her age.

Like her compatibility with Tullio Serafin, the pair’s alliance never risked divergence in creative styles. “Sitting eye to eye, something clicked, something that has never ceased to exist…” Prêtre recalled. “From the word ‘go’ we understood how similar we were in our ways of being musicians… there were never any exasperating debates or preliminary rehearsals: ‘Maria, don’t you think…’ ‘Georges, perhaps here we could…’ and that was enough.”11

To him Maria turned for reassurance during these rehearsals: “Maestro—could I do that at that point? Does it adhere to the French tradition? Maestro, do you think that I could slow down here?” French opera was a quasi-virgin territory for Maria.12

Upon Onassis’ return from the Christina the couple spent Sunday browsing a chateau in Châteaudun, one and a half hours from Paris. Its owner, Fernand Pouillon, was in prison for swindling his company’s shareholders. The ever-observant press alleged Callas was retiring to live with Onassis in one hundred and sixty acres of forest.13

Three days later he was back aboard the yacht14 and she was in recording sessions at the Salle Wagram. It was perhaps not accidentally-on-purpose that Nicole Hirsch—a reporter for French music magazine Chaix Musica—had been dispatched to write about the work. Later Maria was denied admission to the studio when its unwitting guards would not accept her absence of ID. The appearance of Michel Glotz finally saved her.

Walter Legge was also present. Hirsch captured Maria’s recording etiquette: mounting the podium, removing her shoes, crossing her arms. Rehearsing in full voice as always, she informed the journalist: “I’m warming up.”

The orchestra was “stupefied”, according to Walter Legge. “While other singers rarely stop in a recording session—preferring to then re-record and have the prior recording ‘retouched’ with the edits to avoid making the orchestra start again—Maria can sometimes restart an aria ten times consecutively… because a note didn’t seem to go well,” he explained to the hawk-eyed reporter.15

“Tell me if I make a mistake in the French,” Maria had implored Janine Reiss.16 To Pamela Hebert—a student Maria would coach ten years later—she explained it this way: “There's a difference between French music and Italian music; I've learned that on my own experience. In Italian you have to be very clear on the words. In French, the whole phrase passes through more smoothly. If it were Italian music, they would say, ‘Qui m'aurait dit la pla-ce que dans mon cœur’—you're chopping it up. Whereas in French music, it has to be more of a whole phrase.”17

The musical document—originally known as Callas Sings Great Opera from French Arias, later Callas à Paris I—is perhaps the greatest testament to her artistic malleability.

It is not perfect. In this first example of her Carmen “Habanera” acute vocal insecurity is palpable on phrases such as “c’est l’autre que je préfère” (“it’s the other one that I prefer”). Watered down to tones recalling her Rosina in The Barber of Seville, the oddly molded voice transforms what ought to be a femme fatale into a cute coquette.

Paradoxically another track unmasks her exploration of a more erotically calculating character: Delilah from Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. In this take on the biblical tale that sees the High Priest of Dagon use Delilah to distract Hebrew leader Samson from his charge on the Philistines, the woman wallows in sexual dominion. Languid, wistful, sensuously slothful music crafts a carnal creature who exploits not just her assets but the aphrodisiac of the surrounding climate and her primal environs to get exactly what she wants.

“Printemps qui commence, portant l’espérance, aux cœurs amoureux…” (“Spring that dawns and brings hope to the amorous hearts…”) limns Delilah. For the first time we hear Maria use sequential notes contrastingly: “PRIN-temps,” she sings, leaning on the “temps” with a pleadingly desperate, deliberately vulnerable pressure. The sound is as soft as a pedal being freed from a pianist’s grasp.

In each of these instances there is a lean-on: “En vain, je suis BE-lle…” (“In vain, am I beau-tiful…”), “A la nuit TOM-ban…te” (“As night falls…”). Select diminuendi employ a small mouth to connive; evoking a sight of the heroine fanning herself in the sweltering heat; her breath ebbing from torrid fatigue.

Contesting snares of these diminuendi are the antithetically contralto, brazenly conspiratorial tones. It is the voice she uses to accuse Samson of treachery: “Pleurant l’infidèle” (“Weeping for the infidel”), she describes him. The aria ends with a contrast to both of these paradigms as we hear a subtler, more nubile Delilah; one who can only be “saved” by his lovemaking: “A lui ma TEN-dre…sse… Et la douce… iv-RE…sse…” (“To him belongs my TEN-derness… And my sweet ECS-tasy…”). The final words, “Qu’un brûlant amour… garde à son retour” (“That a burning love can keep for his return”) fizzle: a wavering flame in the night wind.

In another aria Delilah reflects on her plan with Maria’s despotic, vibrato-strewn voice: “Samson, recherchant ma présence, ce soir doit venir en ces lieux” (“Looking for me tonight, Samson will come to this place”). Portents percolate these dark tones; diminuendo lends enigma to the slow-to-surface “en… ces lieux” (“in this place”). She commands love—as though love is Cupid—to come “help her weakness… pour poison into his heart!” (“Amour! Viens aider ma faiblesse! Verse le poison dans son sein!”). Her voice is so perversely curved around these words, they peter out in sly diminuendo: she becomes a succubus. A cutting, onomatopoeic “k” sound in the word “es-clave” (“slave”) resounds as harshly as a smacking whip. Delilah is a dominatrix.

It is an ugly voice that sings of Samson’s fears: “He who breaks the chains of a people will succumb to my efforts” (“Lui, qui d’un peuple rompt la chaîne, succombera sous mes efforts”). In its deviation from a natural-sounding timbre the insatiable instrument approximates the bent voice of an unreal beast; descending to the growly pit of an A flat below the middle C.

In “Mon cœur s’ouvre à ta voix” (“My heart opens up to your voice”) the instrument is thinned to forge the spurious impression of Delilah’s innocence. A sensual diminuendo percolates “Redis… à ma tendresse les serments… d’autrefois…” (“Tell… my love again… all that you used to tell me in the past…”). “D’autrefois” (“in the past”) is so soft it suggests a dangerous proximity; Delilah inching closer to her prey.

Over the lengthy legato that makes up “A…ah ré…é…ponds… à…à ma…a…a ten-en-dre…sse” (“Ah… respond to my tenderness”), the sound writhes like a lilypad stirred by a ripple. When Delilah finally bursts through the small talk—dictating the same in a crescendo—it is a euphoric cry; almost climactic.

©Sophia Lambton 2023

The Callas Imprint: A Centennial Biography will be released on her birthday, 2 December.

Hôtel Lancaster, 7 rue Berri, Paris is cited as Callas’ temporary residence in M. Glotz, La note bleue (Paris: Lattès, 2003), 190.

H. Canals, Hommage Maria Callas: 1987 Musée de Neuilly Exhibition Brochure for 16 September–19 October 1987 (Paris: Musée de Neuilly, 1987), 2.

M. Schaeffer, “Aujourd’hui, La Callas,” Elle France, 28 April 1969.

C.-P. Perna, Interview with Janine Reiss for The Maria Callas International Club, 15 November 2003. Accessed at https://www.yumpu.com/fr/document/view/17086723/interview-de-janine-reiss-claveciniste-pianiste-ars-bxl.

D.Fournier, La passion prédominante de Janine Reiss: La voix humaine (Arles: Actes Sud Editions, 2013), 49–54.

Perna, “Interview with Janine Reiss.”

Fournier, 54.

I. Ayre, Entretiens avec Janine Reiss (Lyon: Kirographaires Editions, 2013), 106.

Author’s interview with Janine Reiss, Paris, 19 December 2011.

“Maria Callas commence à la salle Wagram une série d’enregistrements de grands airs,” Le Figaro, 25 March 1961.

V. Crespi Morbio, Maria Callas: Gli anni alla Scala (Turin: Umberto Allemandi, 2008), 5.

N. Hirsch, “Le vrai visage de la Callas,” Chaix Musica, August 1961.

W. Hickey, “Getty Gives Guests a Hint of On Phone Costs,” Daily Express, 27 March 1961.

AP, “The World In Brief,” Guam Daily News, 3 April 1961.

Hirsch, “Le vrai visage de la Callas.”

Interview with Janine Reiss, 28 February 1978, on Hommages à Maria Callas (Paris: EMI France, 1997).